Herschel operating at the second Lagrange point (L2)

Herschel will be stationed at the second Sun-Earth Lagrange point (L2),

1.5 million km from Earth. This point is theoretically stationary in

space with respect to the Earth and Sun, which means that for Herschel,

Earth and the Sun will always be in the same general direction.

This provides a stable thermal environment and a good view of the sky.

Since the Earth is far away, Herschel is not disturbed by its radiation

belts.

At the same time, the spacecraft's position in space and the resulting

temperature extremes make the task of optimising the work environment

for the instruments a challenge.

The Herschel spacecraft has heritage from the successful ESA Infrared Space Observatory (ISO). It has been improved and optimized for a more distant and more favourable orbit and its complement of instruments.

The Herschel spacecraft has heritage from the successful ESA Infrared Space Observatory (ISO). It has been improved and optimized for a more distant and more favourable orbit and its complement of instruments.

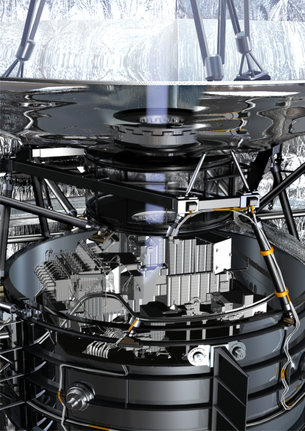

The Herschel satellite is composed of three sections.

First is the telescope, which has a 3.5 m-diameter primary mirror protected by a sunshade. The telescope focuses light onto three scientific instruments; their detectors are housed in a giant thermos flask, known as a cryostat.

The cryostat provides the interface and cryogenic environment for the instrument focal plane units, and supports the telescope, the solar array and telescope sunshade, and a unit of the Heterodyne Instrument for the Far Infrared.

First is the telescope, which has a 3.5 m-diameter primary mirror protected by a sunshade. The telescope focuses light onto three scientific instruments; their detectors are housed in a giant thermos flask, known as a cryostat.

The cryostat provides the interface and cryogenic environment for the instrument focal plane units, and supports the telescope, the solar array and telescope sunshade, and a unit of the Heterodyne Instrument for the Far Infrared.

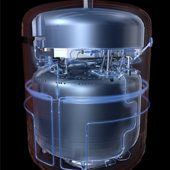

Inside the cryostat, Herschel's detectors are kept at very low and

stable temperatures, necessary for the instruments to operate. The

cryostat contains liquid superfluid helium at temperatures lower than

–271°C, which makes the instruments as sensitive as possible. The

instruments detectors and the cryostat make up the second section, the

payload module.

The infrared detectors must be cooled to extremely low temperatures in order to work, in fact close to absolute zero (–273.15°C or 0 K).

The infrared detectors must be cooled to extremely low temperatures in order to work, in fact close to absolute zero (–273.15°C or 0 K).

All three Herschel instruments will be housed inside and cooled by the

cryostat which is filled at launch with more than 2300 litres of

superfluid helium kept at 1.65 K, i.e. –271.5°C. Further cooling – down

to 0.3 K – is required for the SPIRE and PACS bolometeric detectors. The

role of the cryostat is fundamental because it determines the lifetime

of the observatory.

The superfluid helium evaporates at a constant rate, gradually emptying the tank. It is expected to evaporate completely about four years after launch.

The superfluid helium evaporates at a constant rate, gradually emptying the tank. It is expected to evaporate completely about four years after launch.

When it has all gone, the temperature of the instruments will start to

rise and Herschel will no longer be able to perform observations.

However, the data that Herschel will have supplied will keep astronomers

busy for decades.

The third element of the satellite is the service module located below the payload module. It houses the instrument electronics and the components responsible for satellite function, such as the communication hardware. The service module houses the payload electronics that do not need cooling, and provides the necessary subsystems: power, attitude and orbit control, on-board data handling, thermal control and command execution, communication, and safety.

The third element of the satellite is the service module located below the payload module. It houses the instrument electronics and the components responsible for satellite function, such as the communication hardware. The service module houses the payload electronics that do not need cooling, and provides the necessary subsystems: power, attitude and orbit control, on-board data handling, thermal control and command execution, communication, and safety.

5 March 2013

ESA’s Herschel space observatory is expected to exhaust its supply of

liquid helium coolant in the coming weeks after spending more than three

exciting years studying the cool Universe.

Herschel was launched on 14 May 2009 and, with a main mirror 3.5 m across, it is the largest, most powerful infrared telescope ever flown in space.

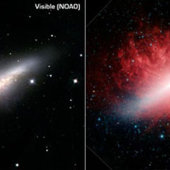

A pioneering mission, it is the first to cover the entire wavelength range from the far-infrared to submillimetre, making it possible to study previously invisible cool regions of gas and dust in the cosmos, and providing new insights into the origin and evolution of stars and galaxies.

In order to make such sensitive far-infrared observations, the detectors of the three science instruments – two cameras/imaging spectrometers and a very high-resolution spectrometer – must be cooled to a frigid –271°C, close to absolute zero. They sit on top of a tank filled with superfluid liquid helium, inside a giant thermos flask known as a cryostat.

Herschel was launched on 14 May 2009 and, with a main mirror 3.5 m across, it is the largest, most powerful infrared telescope ever flown in space.

A pioneering mission, it is the first to cover the entire wavelength range from the far-infrared to submillimetre, making it possible to study previously invisible cool regions of gas and dust in the cosmos, and providing new insights into the origin and evolution of stars and galaxies.

In order to make such sensitive far-infrared observations, the detectors of the three science instruments – two cameras/imaging spectrometers and a very high-resolution spectrometer – must be cooled to a frigid –271°C, close to absolute zero. They sit on top of a tank filled with superfluid liquid helium, inside a giant thermos flask known as a cryostat.

The superfluid helium evaporates over time, gradually emptying the tank

and determining Herschel’s scientific life. At launch, the cryostat was

filled to the brim with over 2300 litres of liquid helium, weighing 335

kg, for 3.5 years of operations in space.

Indeed, Herschel has made extraordinary discoveries across a wide range of topics, from starburst galaxies in the distant Universe to newly forming planetary systems orbiting nearby young stars.

However, all good things must come to an end and engineers believe that almost all of the liquid helium has now gone.

It is not possible to predict the exact day the helium will finally run out, but confirmation will come when Herschel begins its next daily 3-hour communication period with ground stations on Earth.

“It is no surprise that this will happen, and when it does we will see the temperatures of all the instruments rise by several degrees within just a few hours,” says Micha Schmidt, the Herschel Mission Operations Manager at ESA’s European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany.

Indeed, Herschel has made extraordinary discoveries across a wide range of topics, from starburst galaxies in the distant Universe to newly forming planetary systems orbiting nearby young stars.

However, all good things must come to an end and engineers believe that almost all of the liquid helium has now gone.

It is not possible to predict the exact day the helium will finally run out, but confirmation will come when Herschel begins its next daily 3-hour communication period with ground stations on Earth.

“It is no surprise that this will happen, and when it does we will see the temperatures of all the instruments rise by several degrees within just a few hours,” says Micha Schmidt, the Herschel Mission Operations Manager at ESA’s European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany.

The science observing programme was carefully planned to take full

advantage of the lifetime of the mission, with all of the

highest-priority observations already completed.

In addition, Herschel is performing numerous other interesting observations specifically chosen to exploit every last drop of helium.

“When observing comes to an end, we expect to have performed over 22 000 hours of science observations, 10% more than we had originally planned, so the mission has already exceeded expectations,” says Leo Metcalfe, the Herschel Science Operations and Mission Manager at ESA’s European Space Astronomy Centre in Madrid, Spain.

In addition, Herschel is performing numerous other interesting observations specifically chosen to exploit every last drop of helium.

“When observing comes to an end, we expect to have performed over 22 000 hours of science observations, 10% more than we had originally planned, so the mission has already exceeded expectations,” says Leo Metcalfe, the Herschel Science Operations and Mission Manager at ESA’s European Space Astronomy Centre in Madrid, Spain.

“We will finish observing soon, but Herschel data will enable a vast

amount of exciting science to be done for many years to come,” says

Göran Pilbratt, ESA’s Herschel Project Scientist at ESA’s European Space

Research and Technology Centre in Noordwijk, the Netherlands.

“In fact, the peak of scientific productivity is still ahead of us, and the task now is to make the treasure trove of Herschel data as valuable as possible for now and for the future.”

Herschel will continue communicating with its ground stations for some time after the helium is exhausted, allowing a range of technical tests. Finally, in early May, it will be propelled into its long-term stable parking orbit around the Sun.

“In fact, the peak of scientific productivity is still ahead of us, and the task now is to make the treasure trove of Herschel data as valuable as possible for now and for the future.”

Herschel will continue communicating with its ground stations for some time after the helium is exhausted, allowing a range of technical tests. Finally, in early May, it will be propelled into its long-term stable parking orbit around the Sun.

An announcement will follow to confirm when the liquid helium coolant has been exhausted.

Herschel carries three science instruments: HIFI (Heterodyne Instrument

for the Far Infrared), a high-resolution spectrometer; PACS

(Photoconductor Array Camera and Spectrometer); SPIRE (Spectral and

Photometric Imaging REceiver). PACS and SPIRE are both cameras and

imaging spectrometers that together cover the wavelength range 55–672

microns. HIFI covers the two wavelength bands 157–212 microns and

240–625 microns. All three instruments are cooled to –271ºC inside a

cryostat filled with liquid superfluid helium.

Herschel is an ESA space observatory with science instruments provided by European-led Principal Investigator consortia and with important participation from NASA.

For further information, please contact:

Markus Bauer

ESA Science and Robotic Exploration Communication Officer

Tel: +31 71 565 6799

Mob: +31 61 594 3 954

Email: markus.bauer@esa.int

Micha Schmidt

Herschel Mission Operations Manager

European Space Operations Centre (ESOC), Darmstadt, Germany

Email: micha.schmidt@esa.int

Leo Metcalfe

Herschel Science Operations and Mission Manager

European Space Astronomy Centre (ESAC), Madrid, Spain

Email: leo.metcalfe@sciops.esa.int

Göran Pilbratt

ESA Herschel Project Scientist

European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC), Noordwijk, the Netherlands

Tel: +31 71 565 3621

Email: gpilbratt@rssd.esa.int

Herschel is an ESA space observatory with science instruments provided by European-led Principal Investigator consortia and with important participation from NASA.

For further information, please contact:

Markus Bauer

ESA Science and Robotic Exploration Communication Officer

Tel: +31 71 565 6799

Mob: +31 61 594 3 954

Email: markus.bauer@esa.int

Micha Schmidt

Herschel Mission Operations Manager

European Space Operations Centre (ESOC), Darmstadt, Germany

Email: micha.schmidt@esa.int

Leo Metcalfe

Herschel Science Operations and Mission Manager

European Space Astronomy Centre (ESAC), Madrid, Spain

Email: leo.metcalfe@sciops.esa.int

Göran Pilbratt

ESA Herschel Project Scientist

European Space Research and Technology Centre (ESTEC), Noordwijk, the Netherlands

Tel: +31 71 565 3621

Email: gpilbratt@rssd.esa.int

RELATED ARTICLES:

Spanish:

LAS OBSERVACIONES DE HERSCHE PRONTO LLEGARÁN A SU FIN:

5 marzo 2013

Tras pasar más de tres emocionantes años estudiando el universo frío, se

estima que, en las próximas semanas, se agotará el suministro de helio

liquido refrigerante del observatorio espacial Herschel de la ESA.

Herschel fue lanzado el 14 de mayo de 2009 y, con un espejo primario de 3,5 m, es el telescopio infrarrojo más grande y potente jamás lanzado al espacio.

Esta misión pionera ha sido la primera en cubrir todo el rango en la longitud de onda que va desde el infrarrojo lejano hasta el submilimétrico, haciendo posible el estudio de regiones frías de gas y polvo del cosmos antes invisibles, y proporcionando nuevos conocimientos sobre el origen y la evolución de las estrellas y las galaxias.

Con la finalidad de poder llevar a cabo este tipo de observaciones tan sensibles en el infrarrojo lejano, los detectores de los tres instrumentos científicos –dos cámaras/espectrómetro de imagen y un espectrómetro de muy alta resolución – deben enfriarse a una temperatura de –271°C, cerca del cero absoluto. Están en el extremo superior de un tanque lleno de helio superfluido líquido, dentro de un enorme tanque conocido como criostato.

Herschel fue lanzado el 14 de mayo de 2009 y, con un espejo primario de 3,5 m, es el telescopio infrarrojo más grande y potente jamás lanzado al espacio.

Esta misión pionera ha sido la primera en cubrir todo el rango en la longitud de onda que va desde el infrarrojo lejano hasta el submilimétrico, haciendo posible el estudio de regiones frías de gas y polvo del cosmos antes invisibles, y proporcionando nuevos conocimientos sobre el origen y la evolución de las estrellas y las galaxias.

Con la finalidad de poder llevar a cabo este tipo de observaciones tan sensibles en el infrarrojo lejano, los detectores de los tres instrumentos científicos –dos cámaras/espectrómetro de imagen y un espectrómetro de muy alta resolución – deben enfriarse a una temperatura de –271°C, cerca del cero absoluto. Están en el extremo superior de un tanque lleno de helio superfluido líquido, dentro de un enorme tanque conocido como criostato.

El helio superfluido se evapora con el tiempo, vaciando el tanque

gradualmente y determinando el periodo de vida científica de Herschel.

Al lanzarlo, el criostato estaba lleno hasta los bordes con cerca de

2.300 litros de helio líquido (335 kg) lo que garantizaba 3,5 años de

operaciones en el espacio.

De hecho, Herschel ha hecho extraordinarios descubrimientos en un amplio rango de temas, desde galaxias con estallidos de formación estelar en el universo distante hasta nuevos sistemas planetarios en formación orbitando jóvenes estrellas cercanas.

Sin embargo, todo lo bueno llega a su fin, y los ingenieros creen que casi todo el helio líquido se ha gastado.

No es posible predecir el día exacto en el que el helio se agotará por completo, pero la confirmación llegará cuando Herschel empiece su próximo periodo de comunicación diario de 3 horas con las estaciones terrestres.

“No debe sorprendernos cuando ocurra, y cuando pase veremos la temperatura de todos los instrumentos elevarse varios grados en tan solo unas horas”, afirma Micha Schmidt, el Jefe de Operaciones de Misiones de Herschel en ESOC (European Space Operations Centre) de la ESA, en Darmstadt, Alemania.

De hecho, Herschel ha hecho extraordinarios descubrimientos en un amplio rango de temas, desde galaxias con estallidos de formación estelar en el universo distante hasta nuevos sistemas planetarios en formación orbitando jóvenes estrellas cercanas.

Sin embargo, todo lo bueno llega a su fin, y los ingenieros creen que casi todo el helio líquido se ha gastado.

No es posible predecir el día exacto en el que el helio se agotará por completo, pero la confirmación llegará cuando Herschel empiece su próximo periodo de comunicación diario de 3 horas con las estaciones terrestres.

“No debe sorprendernos cuando ocurra, y cuando pase veremos la temperatura de todos los instrumentos elevarse varios grados en tan solo unas horas”, afirma Micha Schmidt, el Jefe de Operaciones de Misiones de Herschel en ESOC (European Space Operations Centre) de la ESA, en Darmstadt, Alemania.

El programa de observación científica fue planeado minuciosamente con el

fin de sacar el máximo partido del periodo de vida de la misión, y

todas las observaciones de alta prioridad ya se han llevado a cabo.

Además, Herschel está llevando a cabo numerosas observaciones de gran interés elegidas específicamente con la finalidad de explotar hasta la última gota de helio.

“Cuando finalicen las observaciones, esperamos haber llevado a cabo 22.000 horas de observaciones científicas, un 10% más de lo planificado en un principio, por lo que la misión ya ha superado sus expectativas”, afirma Leo Metcalfe, Jefe de la Misión y Jefe de Operaciones Científicas de Herschel de la ESA en ESAC (Centro Europeo de Astronomía Espacial) en Madrid, España.

Además, Herschel está llevando a cabo numerosas observaciones de gran interés elegidas específicamente con la finalidad de explotar hasta la última gota de helio.

“Cuando finalicen las observaciones, esperamos haber llevado a cabo 22.000 horas de observaciones científicas, un 10% más de lo planificado en un principio, por lo que la misión ya ha superado sus expectativas”, afirma Leo Metcalfe, Jefe de la Misión y Jefe de Operaciones Científicas de Herschel de la ESA en ESAC (Centro Europeo de Astronomía Espacial) en Madrid, España.

“Pronto las observaciones llegarán a su fin, pero los datos de Herschel

permitirán que se haga una enorme cantidad de ciencia emocionante

durante muchos años”, señala Göran Pilbratt, Jefe Científico del

Proyecto Herschel de la ESA en ESTEC (European Space Research and

Technology Centre) en Noordwijk, Países Bajos.

“De hecho, el pico de productividad científica aún está por llegar, y ahora nuestro trabajo consiste en poner en valor los datos de Herschel tanto como nos sea posible, tanto por la ciencia actual como por la futura”.

Herschel seguirá comunicándose con las estaciones terrestres durante un tiempo después de que se haya agotado el helio, permitiendo una serie de comprobaciones técnicas. Finalmente, a principios de mayo, será impulsado hacia una órbita estable a largo plazo alrededor del Sol.

“De hecho, el pico de productividad científica aún está por llegar, y ahora nuestro trabajo consiste en poner en valor los datos de Herschel tanto como nos sea posible, tanto por la ciencia actual como por la futura”.

Herschel seguirá comunicándose con las estaciones terrestres durante un tiempo después de que se haya agotado el helio, permitiendo una serie de comprobaciones técnicas. Finalmente, a principios de mayo, será impulsado hacia una órbita estable a largo plazo alrededor del Sol.

ESA

- ¿Qué es la ESA?

- Folleto Todo sobre la ESA

- Notas de prensa

- Information Notes

- Pedro Duque

- Participación española misiones ESA

- Presentación de la ESA

- Información para Medios de Comunicación

- Folleto Todo sobre la ESA

- Previsión de actividades 2013

- Folleto de ESAC

- Mensajes clave sobre ESAC

- Solicitud Entrevista

- Imagen científica de la semana

- Fotos de ESAC

- Videos de ESAC

- Presentación de ESAC

- Cómo llegar a ESAC

- Multimedia

- Videos de la ESA

- Euronews Space - en Español

- ESA en Youtube

- Observación de la tierra - Galería de Imágenes

Guillermo Gonzalo Sánchez Achutegui

ayabaca@gmail.com

ayabaca@hotmail.com

ayabaca@yahoo.com

Inside Herschel

Inside Herschel

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario